Following the Mullan Road Through Mineral County

My father never fails to surprise me; and though he is now 82 and I am 58, every time I go out on one of his adventures, he teaches me something new about who I am, where I come from, instills within me a greater sense of my own history, and enriches me with the heritage from which we both have sprung. This past week, he and I spent several days tracking and following the original Mullan Road: from the top of Sohon Pass (now known as Saint Regis Pass, south of the current Lookout Pass knoll and ski area), as it meanders throughout the rocky terrain of Mineral County, and finally continues at the opposite end of the county, just west of Alberton, on a glorious section of the original road preserved as an interpretive walking trail.

My father never fails to surprise me; and though he is now 82 and I am 58, every time I go out on one of his adventures, he teaches me something new about who I am, where I come from, instills within me a greater sense of my own history, and enriches me with the heritage from which we both have sprung. This past week, he and I spent several days tracking and following the original Mullan Road: from the top of Sohon Pass (now known as Saint Regis Pass, south of the current Lookout Pass knoll and ski area), as it meanders throughout the rocky terrain of Mineral County, and finally continues at the opposite end of the county, just west of Alberton, on a glorious section of the original road preserved as an interpretive walking trail.

During his later years, my father’s passion has been to seek out the historical events which have shaped and defined Mineral County. The Mullan Road plays a crucial part in the county’s evolution, as it was the first means by which modern civilization was able to move between the Columbia River at Walla Walla Washington to the Missouri River at Fort Benton Montana. My father had spent most of his life working as a surveyor and engineer for the Montana State Highway Department, in fact his life long project was to work on the current Interstate 90 that runs the length of Mineral County. He retired when the project was completed in 1982. So you could say he has always had an obsession with roads. I remember as a kid spending many long days working and helping him with some of those projects as a flagman or counting loads being hauled in as fill. It wasn’t until he retired he was able to actively explore and find many of the historical sites hidden in our little valley.

Lt. John Mulllan and the Mullan Road

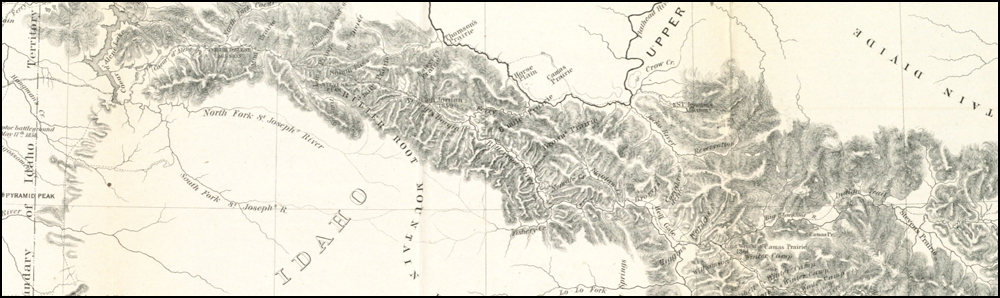

In 1859 Lt. John Mullan (an American soldier, explorer, civil servant, and road builder; who had years earlier joined the Northern Pacific Railroad Survey, led by Isaac Stevens) hired more than 80 civilians for a road construction crew to forge new road across a vast under-explored frontier. The crew included carpenters, cooks, herders, laborers, teamsters, and topographers. The Army provided an escort which consisted of 100 soldiers and 40 packers and teamsters, who were also offered extra pay if they worked as construction labors. Mullan acquired 180 oxen and dozens of cattle, horses, and mules.

They began scouting the route on May 16, and construction began on July 1. Finding a good pass through the mountains was a major obstacle Mullan faced after pushing the road east from the Coeur d'Alene Mission, and Mullan sent Gustav Sohon ahead to scout a path through the Bitterroot Mountains. Sohon discovered a way up and over the mountain at what is now St Regis Pass, it was a steep climb up the, now, Idaho side, sho steep they had to make two switchbacks to get to the top and a then another steep decent down into the, now, Montana side. Mullan originally named it "Sohon Pass" in honor of his friend; and my father is still trying to get it renamed back to that original name. Moving forward toward Sohon Pass, Mullan’s construction party found the timber incredibly dense, and the trees very large in diameter.

My father drove me up to Lookout Pass and we followed the railroad grade around the side of the mountain to an area currently under construction, being expanded into a commercial ski area. We hiked to the top of the ridge and I got my first glimpse into this elusive road and walked to what remains of Sohon’s Pass.

The ground covered in snow. We could see the path, barely distinguishable but unmistakably cut through the dense forest 160 year earlier. I would have never known of its existence had my father not pointed it out, but then once I spotted it, it was quite obvious. My father has been working with the Forest Service and the Ski Resort to preserve these sections of the old road. Though the ski area is cutting vast swaths through it, there it remains in tact, barely walkable, bestrewn with fallen trees and a century plus of overgrowth.

The ground covered in snow. We could see the path, barely distinguishable but unmistakably cut through the dense forest 160 year earlier. I would have never known of its existence had my father not pointed it out, but then once I spotted it, it was quite obvious. My father has been working with the Forest Service and the Ski Resort to preserve these sections of the old road. Though the ski area is cutting vast swaths through it, there it remains in tact, barely walkable, bestrewn with fallen trees and a century plus of overgrowth.

The Winter of 1859-1860

On November 3rd 1859, 15 to 18 inches of snow fell. As the snow continued to fall for a week, and the temperature dropped below 0 °F, food supplies dwindled, and the supply train with winter clothing was delayed. Having cut the road through roughly 80 miles of forest and mountains, Mullan's crew called a halt near modern-day De Borgia Montana, and constructed residential huts, a log cabin office, and a storehouse in a protected area called Cantonment Jordan. The weather was turning into a grueling winter. Most of the cattle, horses, and mules died; what few cattle survived, the men butchered. A few men were sent to herd the remaining horses and mules to the Bitterroot Valley, where temperatures would be warmer and the snow less deep. Although the supply train with winter clothing and more supplies did eventually reach Cantonment Jordan; the party was forced to leave their supplies at the foot of the pass because the exhausted animals could not continue, and Mullan had his men build 20 slabs, and they manually hauled the supplies to the camp.

The next 3 months were particularly harsh. By December 5th, the temperatures plunged to -40 °F below. The 5 feet snow at the top of the pass in December accumulated to a 7 feet depth by January. Many of the workers suffered sever frostbite, and despite the incredible hardship, Mullan’s men continued to work with little complaint. 25 soldiers came down with scurvy from eating too much salted meat and too few vegetables but Mullan had vegetables transported from the Coeur d'Alene Mission to end the scurvy.

Following A Road Forged 160 Years Eariler

My father and I walked the area that must have once contained the vast complex of Cantonment Jordan. Though we found remnants of what may have been the old road, now on private property; we were unable to find any signs of structural remains. It is an area that would have been protected from the winds with mountains at its back, but not from the harshness of winter elements.

We then drove through the valley on the Camel’s Hump Road at Henderson toward St Regis. My father stopped and we walked through a dense cedar forest into an area he thought must have been part of the Mullan Road.

We finished that day in St Regis on the banks of the Clark Fork River at the landing where Mullan’s crew had built a ferry to cross the river.

We finished that day in St Regis on the banks of the Clark Fork River at the landing where Mullan’s crew had built a ferry to cross the river.